The Massacre

Introduction

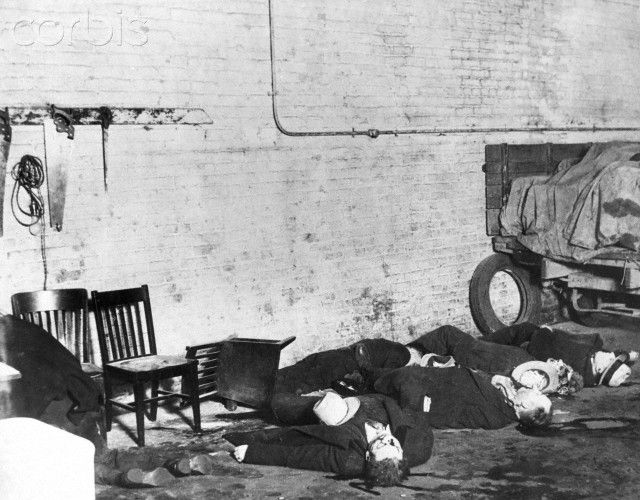

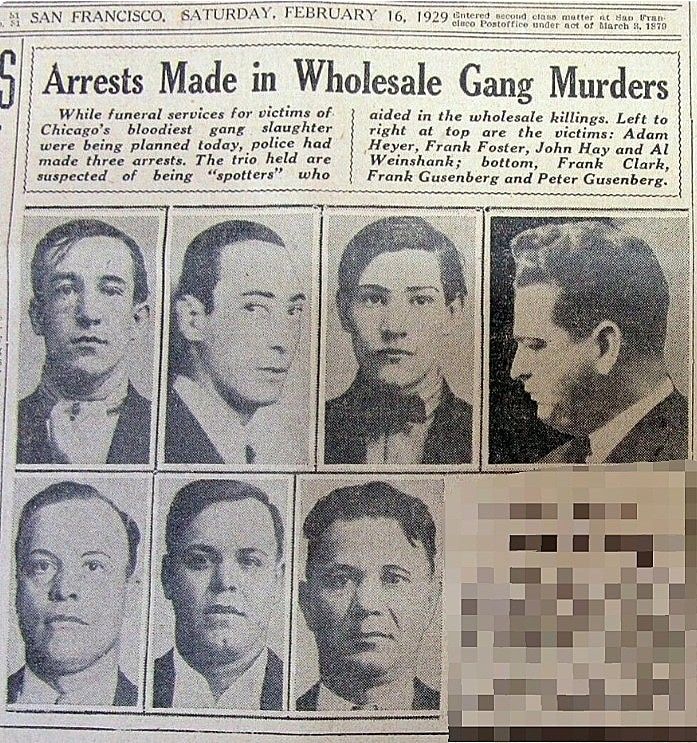

The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre remains one of America’s most gruesome and analyzed criminal events. On February 14, 1929, at dawn, seven men from Chicago’s North Side Gang were executed with machine guns in a garage by disguised police officers. The massacre, allegedly ordered by Al Capone, was more than an act of violence—it was a psychological experiment in fear, control, and organized crime behavior.

Almost a century later, criminologists and behavioral experts still study this event as more than a gangland killing. It stands as an unwitting social experiment

that revealed how power, loyalty, and fear can influence human choices and shape entire criminal systems.

Historical Background

To understand the roots of the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, we must step into Chicago’s turbulent 1920s. During Prohibition, alcohol became a black-market empire. Gang leaders such as Al Capone and George “Bugs” Moran turned crime into business, running violent monopolies. The growing tension between Capone’s South Side gang and Moran’s North Side gang reached its deadly climax on that February morning.

What made the massacre unique was not just the violence—it was the illusion of authority. The attackers posed as police officers, blurring the line between law and crime. This deception introduced a new level of psychological manipulation, later analyzed by criminologists as part of what became known as the “St. Valentine’s Day Massacre Experiment.”

Fear as a Weapon

In behavioral psychology, fear is one of the most powerful motivators of human behavior. Fear became Capone’s most effective weapon. His intention went beyond killing Moran’s men; it was to send a chilling message to every rival gang—that defiance meant death.

This was psychological conditioning in its purest form: a visible act of terror that trained Chicago’s underworld to associate resistance with annihilation. Much like classical conditioning, Capone’s display made fear synonymous with obedience. The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre deaths thus changed the emotional landscape of organized crime—violence was no longer just punishment; it became a tool of control.

Power and Obedience

The massacre echoes later psychological studies such as Stanley Milgram’s obedience experiment (1961) and Philip Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment (1971). Both proved how ordinary people could commit extreme acts when directed by authority.

In Chicago, Capone’s men followed orders for the same reasons—discipline, loyalty, and the belief they served a higher purpose. Their obedience was driven by identity and power rather than morality. The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre summary thus reveals how organized crime mirrored real-world social psychology: people obey not because they agree, but because they belong.

The Illusion of Loyalty

Loyalty was one of the key psychological levers of this tragedy. Sociologists call this “collective identity”—a sense of belonging so strong it overrides personal ethics. In the North Side and South Side gangs, loyalty was non-negotiable. Betrayal meant death.

The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre victims died because of their loyalty to Moran, while Capone’s men killed because of theirs. This paradox remains a hallmark of criminal psychology—where loyalty becomes both a virtue and a trap. Even today, in modern crime rings and extremist groups, people suppress morality for the illusion of unity and power.

Beyond the Fear of Death

After the massacre, Capone’s empire expanded without open resistance. Rival gangs avoided confrontation, and the city entered a period of uneasy silence. Psychologists describe this as negative reinforcement—people complied to avoid pain. The fewer the challenges, the stronger Capone’s psychological control grew.

The massacre produced measurable behavioral outcomes: less open gang warfare, more centralized criminal power, and a deepened culture of fear. It demonstrated that obedience could be achieved not by persuasion but by terror.

Lessons for Modern Criminology

Experts studying the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre wall and historical evidence see more than bloodshed—they see a laboratory of human power dynamics. The event showed that:

-

Fear can be more effective than law.

-

Authority symbols can demand blind obedience.

-

Group loyalty can erase moral judgment.

These lessons continue to shape modern criminology and behavioral psychology.

Ethical Reflections

Every experiment—intentional or accidental—raises ethical questions. The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre forces us to ask: When does power become cruelty?

For Al Capone, the massacre was strategy; for psychologists, it became a case study in moral collapse. Like Milgram’s participants who believed they were “just following orders,” Capone’s gunmen believed they were fulfilling duty. The event humanized both killers and victims, showing how obedience can strip people of moral awareness.

The Legacy of Fear and Power

The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre wall location has since become a grim symbol of loyalty and fear. Historians, criminologists, and tourists visit it as a reminder that violence is not only physical but also psychological. Power works not just through guns but through belief, conformity, and fear.

Nearly a century later, the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre photos still haunt public memory—an eternal lesson on how quickly obedience can eclipse ethics.

Conclusion

The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre Experiment stands as the ultimate example of how organized crime, fear, and loyalty intersect to shape human behavior. It was not only a historical event but also a psychological mirror showing what happens when power dominates morality.

The massacre teaches that control often begins in the mind, that obedience can become more dangerous than violence, and that loyalty—when twisted by fear—can trap people inside systems of cruelty.